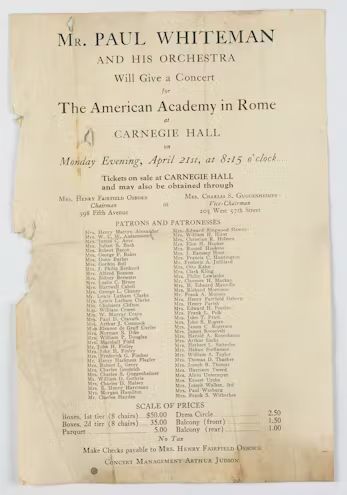

One hundred years ago, on February 12th, a cold and snowy day in New York City, a large crowd gathered at Aeolian Hall, across from Bryant Park. Among the audience were famous figures like composers Sergei Rachmaninoff and John Philip Sousa, violinist Jascha Heifetz, conductor Leopold Stokowski, and actress Gertrude Lawrence. It’s said that hundreds more couldn’t even get in. They had all come to attend a concert led by the famed conductor Paul Whiteman. In his memoir, Whiteman wrote: “My goal with this concert was to show skeptics how popular music had evolved from the chaotic early days of jazz into its current melodic form.”

You might wonder whether Whiteman was trying to sanitize jazz’s popular roots for elite audiences comfortably seated in the temple of classical music.

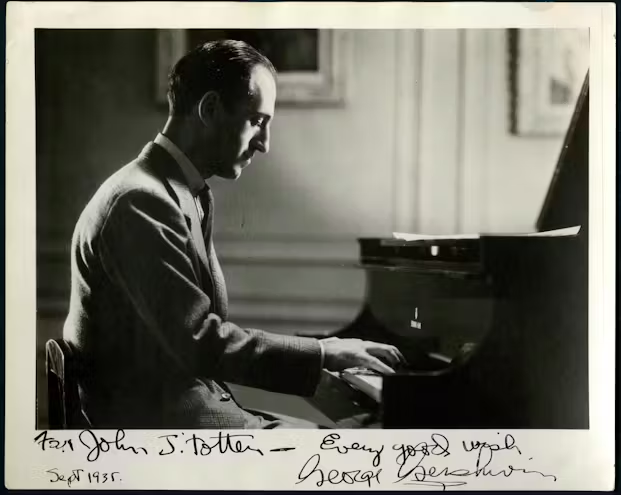

But the audience was in for a surprise. Near the end of the program, a screeching clarinet glissando soared upward—the unmistakable opening of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. It was a piece brimming with potential—not just for the composer, but for the very future of American music.

Joseph Horowitz, author of Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall, says, “Gershwin knew exactly what he was doing, and he truly didn’t care what people thought. He wanted to bridge musical worlds that were otherwise separate.” These worlds included jazz, the pop music of the time, and classical music—and Gershwin fused them. Rhapsody in Blue received a thunderous ovation and became a concert staple for Whiteman for years. Gershwin’s later works—An American in Paris, Concerto in F, Cuban Overture, and the opera Porgy and Bess—would further his vision of musical synthesis.

Horowitz acknowledges, however, that Gershwin faced rejection from America’s classical music establishment.

“Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, and Leonard Bernstein all treated Gershwin as if he were a musical dilettante—not someone to be taken seriously,” he says. They believed jazz wasn’t serious music, and that Gershwin’s blending of it with classical music was akin to “poisoning the well.”

Bernstein, in a 1955 essay, wrote: “You know this rhapsody isn’t the product of a rigorous composer. It’s a collection of paragraphs held together by flour paste.”

While audiences embraced Rhapsody in Blue from the start, critics were far more divided. In The New Republic, Paul Rosenfeld called it “circus music… vague in its ideas and recycled exuberance,” adding that it was “not serious music, but jazz in disguise.”

Attitudes toward Gershwin had lasting consequences for classical music in America. In the 1920s, white composers had the opportunity to draw from the rich musical traditions of Black America—but most did not. Except Gershwin.

Horowitz argues that understanding the constraints on American classical music between the two World Wars is key: “Classical music in the U.S. never fully developed a native identity. That’s why I argue it still remains marginalized today.”

This also raises the issue of cultural appropriation. Was Gershwin stealing from Black culture? And as later generations of Black musicians began borrowing Gershwin’s chord progressions, how should we view that relationship?

Trumpeter and composer Terence Blanchard, who navigates both jazz and classical realms, says: “It’s not something we talk about enough.” In 2021, he became the first Black composer to have an opera staged at the Metropolitan Opera. “When you say cultural appropriation, you’re implying someone took music without crediting its originators. I don’t think that’s Gershwin.”

Part of Gershwin’s musical identity came from his time spent in Harlem, where he was captivated by the vibrant “stride” piano style—a blend of ragtime, blues, and folk elements.

Lara Downes, a pianist who has performed Rhapsody in Blue numerous times and is currently touring with a new version of it, says: “I hear more than just jazz in Gershwin’s piece—I hear politics.” She notes that just three months after the rhapsody premiered, the Johnson-Reed Act was passed—a xenophobic immigration law that effectively shut down Ellis Island, halted immigration from Asia, and sharply curtailed arrivals from Southern and Eastern Europe.

Gershwin himself was a second-generation Russian immigrant. Speaking with his biographer Isaac Goldberg, he described Rhapsody in Blue as “a musical kaleidoscope of America.” You can hear the sounds of Tin Pan Alley, where he worked as a song plugger as a teenager, as well as influences from Yiddish theater, Spanish music, barrel organs from the Lower East Side, and, of course, jazz.

Gershwin died of a brain tumor in 1937, at just 38 years old. Who knows what American classical music might sound like today if he had lived longer—or if American composers had taken both him and the Black musical traditions that inspired him more seriously.